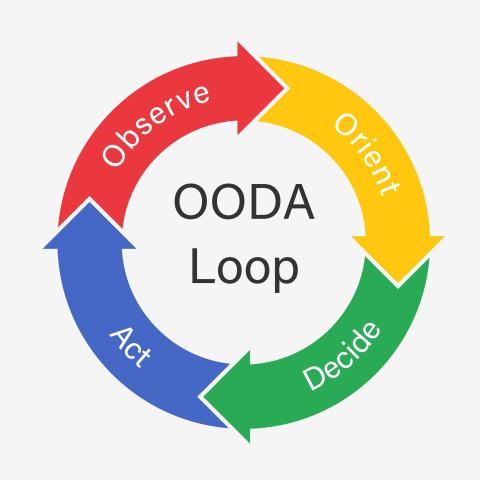

In 2017, I wrote a five-part series called People > Machines that argued something unfashionable: that human beings are more important than the technology they wield. In Part Three, I made the case that if military OODA loops apply to cyber-crime, a human brain assisted by machines will always outposition machine-only adversaries. That the human mind's ability to Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act across high-dimensional problem spaces gives it an advantage that raw computational speed cannot replicate.

Eight years later, I believe that more than ever. I also believe we're about to learn a very expensive lesson about what happens when the OODA loop meets its evil twin.

The Feedback Loop Nobody Talks About

Here's the thing about OODA loops. They work beautifully when the principles driving each phase are sound. A fighter pilot observes the threat environment, orients based on training and doctrine, decides on a course of action, and acts. The loop repeats, each cycle faster and more refined than the last. This is a positive feedback loop in the best sense. Competence builds on competence. Speed compounds with accuracy.

But positive feedback loops are morally neutral. They don't care whether the signal they're amplifying is good or bad. Put a microphone too close to a speaker and you don't get better sound. You get a shriek that'll clear the room. The same physics that makes a well-tuned amplifier sing will make a poorly tuned one destroy itself.

I've spent the last six months building WitFoo's analytics platform with Claude Code. I've migrated legacy codebases into AI-assisted workflows. I've written about why AI isn't stealing my job or my soul. I am fully invested in the promise of AI-assisted development. And from that vantage point, I can tell you with confidence that the OODA loop metaphor I applied to cybersecurity operations in 2017 applies with terrifying precision to AI-assisted software development in 2026.

The difference is the stakes. When the loop goes right, it goes spectacularly right. When it goes wrong, it goes wrong at a speed that would make your head spin.

From Five Commits to Five Hundred

Let me put some numbers to this. Before AI-assisted development, a typical developer might produce five to ten meaningful commits per week. With Claude Code and structured workflows, I regularly see 100 or more. That's not a marginal improvement. That's an order of magnitude acceleration in the OODA loop cycle time for software development.

Now think about what that means through the lens of feedback loops. Every commit is a cycle through observe-orient-decide-act. The developer (or the AI, guided by the developer) observes the current state of the code, orients based on project standards and requirements, decides on a change, and acts by writing and committing code. The faster the cycle, the more opportunities to compound.

If your orientation phase is grounded in solid principles (rigorous linting, comprehensive testing, security scanning, clear documentation standards), then each cycle reinforces quality. The tests catch issues before they propagate. The linter enforces consistency. The security scans close vulnerabilities before they compound. Each commit makes the next commit safer, cleaner, and more reliable. This is the OODA loop at its finest. Disciplined operators using powerful tools to achieve outcomes neither could achieve alone.

If your orientation phase is grounded in poor principles (or worse, no principles at all), then each cycle reinforces dysfunction. No linting means inconsistent code piles up 20 times faster than before. No testing means bugs compound and cascade at a rate that makes manual debugging nearly impossible. No security scanning means vulnerabilities multiply geometrically instead of arithmetically. Each commit makes the next commit more dangerous.

This is the microphone-next-to-the-speaker scenario. The amplification is real. The signal being amplified is garbage.

The Amplifier Doesn't Judge

Back in Part One of the original series, I wrote about how businesses spent billions on cybersecurity products hoping machines would solve the problem so they wouldn't have to invest in people. The machines didn't solve it. They generated thousands of useless alarms that buried the humans who eventually arrived to do the actual work. The tools became taskmasters instead of enablers.

The same dynamic is playing out right now with AI coding tools, just faster and with higher stakes.

I talk to developers who are using AI assistants without a linter configuration, without a test suite, without documented coding standards. They're prompting Claude or Copilot or whatever tool they prefer and shipping the output directly. It works, in the same way that driving without a seatbelt works until it suddenly doesn't. And when it stops working, they won't have five commits worth of technical debt to untangle. They'll have five hundred.

I learned this the hard way myself. In my post on coding with Claude, I was honest about things coming off the rails multiple times. Claude will confidently introduce bugs, hallucinate features you didn't ask for, and occasionally break things that were working perfectly. What saved us wasn't the AI. It was the human-built infrastructure around the AI: the testing pyramid, the CLAUDE.md documentation, the WitFoo Way standards document, the phased workflow that forces review at every stage.

The infrastructure is the orientation phase of the OODA loop. Get it right and the loop is a virtuous cycle. Skip it and the loop is a death spiral.

Turning Fire into a Forge

I don't want to be all doom and gloom here, because the upside is genuinely extraordinary. When robust devops practices are in place, the fires from those accelerated feedback loops become something powerful and productive.

Security gets better. Not incrementally, but dramatically. When every PR runs through automated security scans, and you're producing 20 times more PRs than before, you're catching and remediating 20 times more vulnerabilities. The OODA loop for your security posture tightens from weeks to hours.

Documentation gets better. I wrote in my legacy migration post about how documentation quality compounds. Each AI session benefits from every previous session's documentation updates. The more you use Claude, the smarter Claude gets about your system (assuming you're disciplined about capturing what it learns). That's a positive feedback loop feeding knowledge back into the orientation phase, which is exactly where you want it.

Performance gets better. When you have performance benchmarks built into your test suite, every commit gets measured. Regressions get caught immediately. Optimizations compound across hundreds of commits instead of dozens. Our analytics platform processes billions of signals daily, and the performance characteristics were refined through hundreds of test-driven iterations that would have taken years at manual development speed.

Supportability gets better. Code that's tested, documented, and consistently structured is code that a support team (human or AI-assisted) can actually troubleshoot effectively.

Whatever you do well manually gets amplified when you go from five commits a week to 100 or more. Whatever you do poorly gets amplified just as aggressively.

Ask the Right Question

Here's where the human element becomes absolutely critical, and why I stand by my 2017 thesis that People > Machines.

You have a choice when you adopt AI-assisted development. You can ask AI to accelerate your existing practices. Or you can ask AI to help you find and repair the problems in your existing practices. This choice determines whether you hit tech-debt bankruptcy or build something exceptional.

If your devops pipeline has no linting, ask Claude to help you build a comprehensive linting configuration before you write a single line of feature code. If your test coverage is spotty, ask Claude to audit your codebase and generate a testing plan. If your security practices are ad hoc, ask Claude to implement systematic security scanning. If your documentation is sparse, well, as I wrote in the legacy migration post, documentation is the one task that human developers resist most and Claude genuinely excels at.

This is the Wizard's job, not the Warrior's. The Wizard decides what to build and why. The Warrior executes. If the Wizard points the Warrior at the right problems (fixing your devops, establishing your testing infrastructure, documenting your architecture), then every subsequent cycle of the OODA loop gets cleaner and faster. If the Wizard points the Warrior at shipping features without infrastructure, the loop accelerates toward a cliff.

At WitFoo, we spent months building testing scripts, linter configurations, documentation frameworks, and the WitFoo Way standards document before we started accelerating feature development. It felt slow at the time. In retrospect, it was the most important work we did. Every session since has benefited from that foundation.

The Human in the Loop Is Not Optional

In Part Three of the original series, I wrote that the human brain is not as quick as a computer but is much more resilient, agile, and innovative. I argued that cyber-criminals succeed because they recognize the superiority of the human mind to adapt faster than computers.

The same principle applies here. AI coding tools are extraordinarily fast but they lack judgment about what matters. They don't know whether your project values security over speed, or stability over features, or maintainability over cleverness. Those are human decisions. Those are the orientation principles that determine whether the OODA loop is constructive or destructive.

Every time you sit down with an AI coding tool, you're setting the orientation for a high-speed OODA loop. The principles you bring to that session (your testing standards, your security requirements, your documentation expectations, your definition of done) determine what gets amplified. The AI doesn't care. It will happily build beautiful, well-tested, secure code or it will happily build a towering pile of technical debt that looks great on first glance and collapses under production load.

The human decides which one.

Wrap Up

I wrote People > Machines eight years ago because I saw an industry that was over-investing in tools and under-investing in the craftspeople who wield them. That thesis hasn't changed. If anything, the arrival of AI-assisted development has made it more urgent.

The OODA loop is a powerful concept because it describes how iterative cycles of observation, orientation, decision, and action can create compounding advantages. But the concept is neutral. It compounds whatever you feed it. Feed it disciplined practices, rigorous testing, and clear standards, and you get a forge that turns raw material into something remarkable. Feed it sloppy habits, absent guardrails, and wishful thinking, and you get a blowtorch pointed at your own feet (at 20 times the speed you used to burn yourself).

The choice isn't whether to adopt AI-assisted development. That ship has sailed. The choice is whether to invest in the human infrastructure (the principles, the practices, the judgment) that determines what the AI amplifies. Build your testing. Configure your linters. Document your standards. Audit your security. Do it before you start shipping features at AI speed.

Then let the loop run. It'll sing.

Charles Herring is co-founder and CEO of WitFoo, a cybersecurity company building collective defense solutions. He is a US Navy veteran and speaks regularly at security conferences including DEFCON, GrrCON, and Secure360. You can find him on LinkedIn.